“Odds of achieving sugar-sweetened beverage but not water recommendations are greater among individuals with a chronic disease” – finds new VT study

A new study from Dr. Brenda Davy (Associate Professor – HNFE, former director – Water IGEP) and colleagues titled “Associations Among Chronic Disease Status, Participation in Federal Nutrition Programs, Food Insecurity, and Sugar-Sweetened Beverage and Water Intake Among Residents of a Health-Disparate Region” was published in the Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior.

The cross-sectional study looked at residents in the medically underserved rural area of Dan River Region (spread across south central VA and north central NC) and measured adherence to water and sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) recommendations vis-a-vis whether they suffered from one or more chronic illnesses, were part of federal nutrition programs, had food insecurity, and sociodemographic characteristics.

I sat down with Dr. Davy to get a perspective on the findings for scientists and laymen alike.

1 – What was your motivation behind explicitly evaluating adherence to SSB and water-intake recommendations in the Dan River Region?

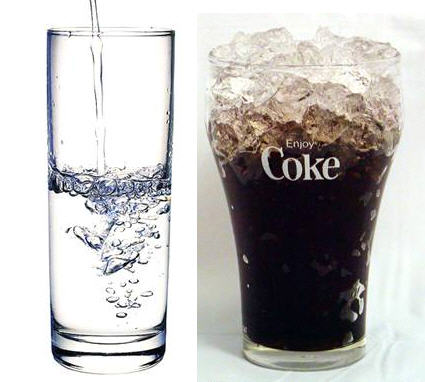

The Dan River region is federally designated as a “medically underserved” area – it is a disadvantaged, “health disparate” region in the US, with a high prevalence of obesity and related chronic diseases, such as type 2 diabetes. It is also economically disadvantaged, with high rates of poverty and unemployment. We were particularly interested in beverage consumption in this population for several reasons – the first is that SSB are linked to weight gain and many adverse health outcomes, so we wanted to evaluate SSB consumption in this population as it might be a good target for dietary intervention. The second is that since tap water is widely available at little to no cost, this could be a great alternative beverage to SSB consumption, with both health and economic benefits (if it were used to replace SSB). But usual water intake habits of residents in this area were not known.

2 – How were the specific criteria of chronic disease status, food security status and participation in federal nutrition programs chosen?

These were all self-reported, based upon questions used by the CDC in their health surveillance studies. We adapted the questions for this study.

3 – What are the current water and SSB-intake recommendations for the general public? Are these widely known and how are they usually communicated?

The American Heart Association has SSB intake recommendations – less than 100 kcal/day for women, and less than 150 kcal/day for men. Water intake recommendations are less clear-cut, so we used a recommendation by the Beverage Guidance Panel (Am J Clin Nutr 2006), which recommended a minimum intake of 20 fl oz tap water per day. The Institute of Medicine has a general recommendation for fluid intake – of about 9 cups/d for women and 13 cups/d for men – but that is total beverage fl oz and not just water.

4 – For the statistics geeks, can you briefly tell us how your data in nutrition and beverage consumption studies are usually mined for patterns? How were models chosen and results analyzed for this study?

For this study, we used logistic regression models to predict odds of meeting SSB and water guidelines, while controlling for demographic factors that often relate to beverage intake (such as age and gender). We can use other approaches as well – linear regression to predict SSB calories or water fl oz – in this type of cross-sectional study.

5 – What do your findings suggest about individuals with chronic diseases and their adherence to water and SSB intake recommendations?

We were interested in whether or not individuals who were “connected” in some way to a system which provided nutritional guidance (or should be providing nutritional guidance!), to determine whether or not they were more likely to meet healthy beverage intake guidelines than others in their region. That was why we were interested in SNAP or WIC (federal nutrition programs) and people with chronic diseases, who are likely accessing medical systems. Unfortunately, SNAP or WIC participation did not seem to predict whether or not individuals met SSB guidelines, although individuals with some chronic medical conditions were more likely to meet SSB recommendations. So the take home point may be that with federal nutrition programs, more attention should perhaps be devoted to promoting healthy beverage consumption patterns.

6 – What barriers do you think prevent increased adoption of water and SSB-intake recommendations for the American population – whether living in health-disparate region or otherwise?

Water safety, or perceptions of water safety, may be a big issue!