Improving Consumer Lexicon to Describe Aesthetic Issues in Water Quality

By Katherine Phetxumphou, Ph.D. candidate of Civil Environmental Engineering and Water IGEP, presented at 11th IWA Symposium on Tastes, Odours & Algal Toxins in Water in Sydney Australia on February 2017

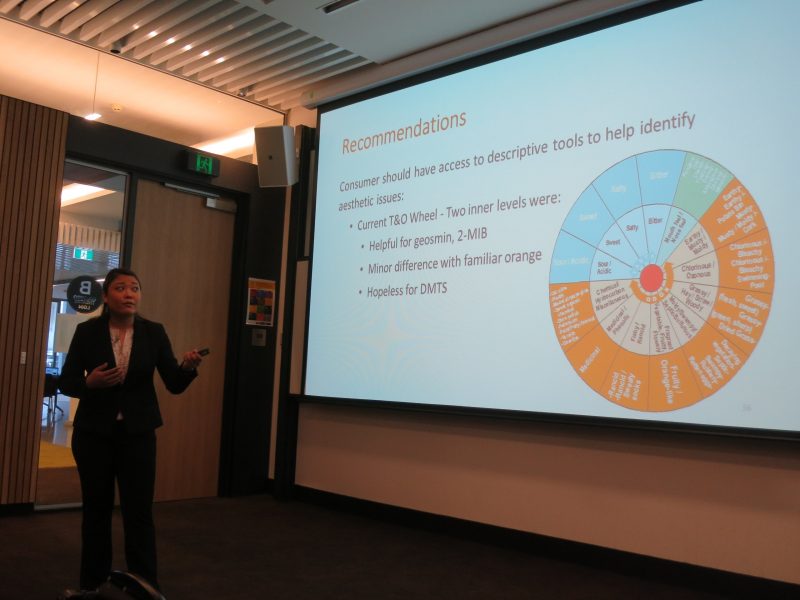

Introduction: Published food and beverage Taste-and-Odour (T&O) Wheels, and associated lexicons, were developed to summarize sensory qualities and organoleptic characteristics unique to foods and beverages (Drake and Civille 2003; Lawless and Civille 2013), including beer, scotch whiskey, wine, and drinking water. The drinking water industry’s attention focuses on characterizing eight major general categories of aesthetic issues: earthy-musty, chlorinous, grassy, sulfurous/septic, fragrant/vegetable, fishy/rancid, medicinal, and chemical (Mallevialle & Suffet 1987; Khiari et al. 2002; Standard Method 2170, APHA 2012). The inner drinking water T&O Wheel has eight general categories of odours, four tastes, and mouth feel. The middle ring indicates specific descriptors for each of the general categories of odours and taste. There is a third outer ring with chemical names and reference standards. This tool is available to water personnel, but most consumers do not know that it exists.

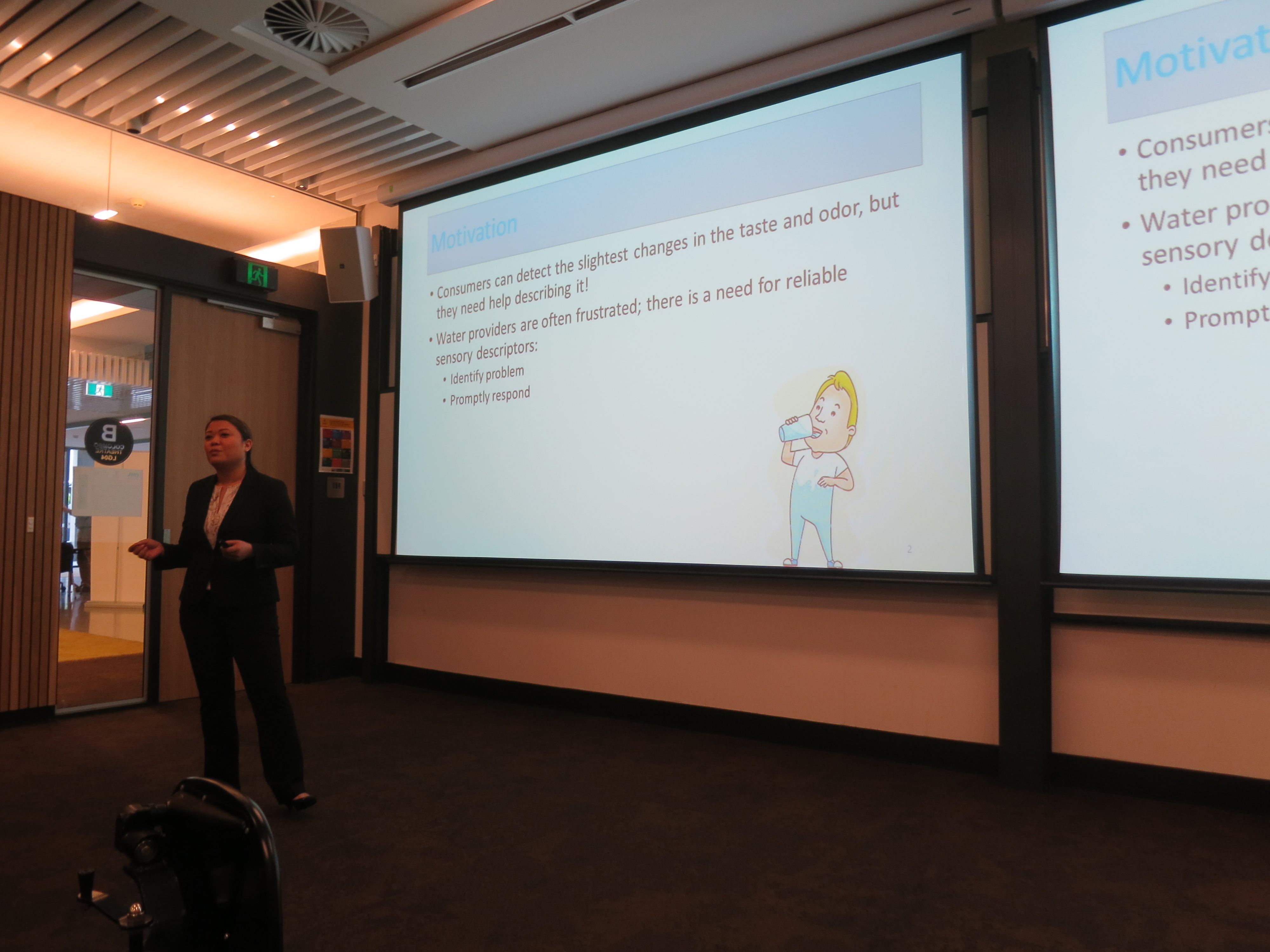

Globally, consumers are first responders and experts at detecting changes in aesthetic water quality, but are often challenged to provide accurate descriptions due to unfamiliar lexicons and unexpected odours in their drinking water. Consumers sometimes can provide valuable feedback on water off-flavors and odours (Burlingame & Mackey 2007; Yu et al. 2014; Dietrich and Burlingame 2015; Piriou et al. 2015; Phetxumphou et al. 2016), and other times, consumers find it difficult to effectively describe off-flavors and odours in drinking water (Burlingame 2015; Gallagher and Dietrich 2014; Dietrich et al. 2014; Burlingame 2015; Webber et al. 2015). Average drinking water consumers are naïve as they lack the experience and the vocabulary to accurately describe odours, especially when unexpected odours are present (Köster et al. 2002; Köster 2005). Thus, this research focuses on improvements to methods and tools that can help water personnel and consumers describe odourants in drinking water.

Methods and Materials: The odourants investigated are common odours detected in drinking water and present on the T&O wheel (Khiari et al. 2002; APHA 2012). 2-MIB is a musty odourant (APHA 2012); geosmin is an earthy odourant (APHA 2012); orange extract with limonene is a citrus-orange-lemon odourant (Dravnieks 1992); and dimethyltrisulfide (DMTS) has unpleasant onion, garlic, sulfur, septic, rotten egg descriptors (Dravnieks 1992; Dietrich et al. 2014; Watson and Jüttner 2015). In the first odour sensory study, fifty naïve consumers sniffed vials with common odour standards and responded to a “pre-training” response form that asked for demographic information and odourant descriptors. Forty milliliter amber volatile organic analysis vials were prepared a day before the sensory test. Each odour vial contained a cotton ball absorbing each odourant. Subjects sniffed the odour vials in random order at room temperature. They waited at least 2 minutes between sniffing of odourants. After several months, in a second odour sensory test, the same group was trained to use the Drinking Water Taste and Odour (T&O) Wheel and asked again to sniff and describe the same odourants. Subjects also completed a “post-training” questionnaire that included questions for them to rate the helpfulness of the T&O Wheel in describing the odourants.

Correct responses to odourant descriptors were based on words on the T&O Wheel and from the Atlas of Odours Character Profiles (Dravnieks 1992), which is a compilation of odour descriptors for common reference standards in the food and beverage industry developed by a panel of trained sensory experts and contained more detailed descriptors than the T&O Wheel. Statistical analysis used McNemar’s test to determine if the T&O Wheel was an effective tool in aiding consumers in describing the odourants. Consumer responses were compared to two lists and measured for correctness: 1) “pre-training” responses with “post-training” responses using correct words from only the T&O Wheel; 2) “pretraining” responses using only T&O Wheel words with “post-training” responses using T&O Wheel descriptors and descriptors from the Atlas of Odours.

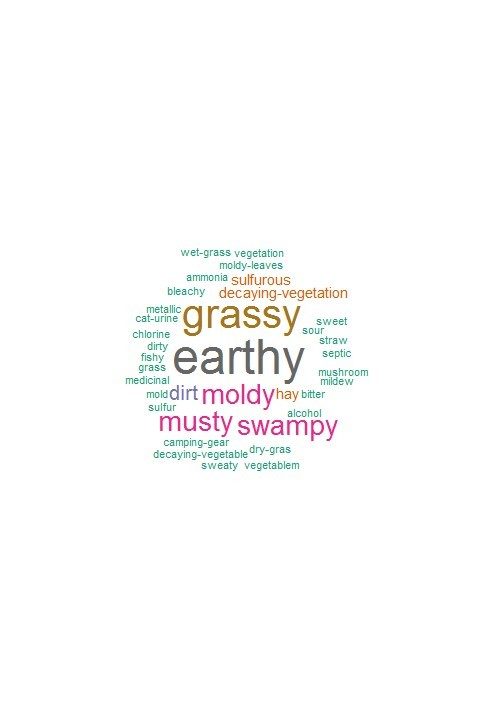

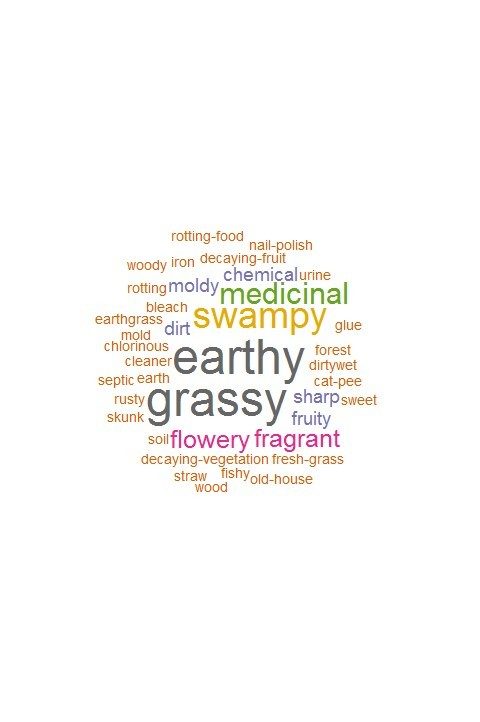

Results: Results revealed that consumers were equal at describing orange with or without the T&O Wheel as citrus, orange-like. McNemar’s test showed that the T&O Wheel did improve consumers’ descriptors of orange, but with additional descriptors present in the Odour Atlas over the T&O Wheel, the addition of Odour Atlas words can improve consumer description. Descriptors for geosmin (Figure 1a) and 2-MIB (Figure 1b) initially varied from “official” earthy/musty to medicinal, camphor, chlorine, but were more consistent after applying the T&O Wheel. McNemar’s test confirmed that the T&O improved consumers’ descriptors of geosmin and 2-MIB, and the addition of the Odour Atlas made no difference since same correct descriptors were present in both. Dimethyltrisulfide has “official” septic-swampy descriptors and varied with sewage to propane and chemical, but consumer descriptors were not more consistent after using the T&O Wheel as seen by the McNemar’s test. Including additional DMTS descriptors from the Odour Atlas does show a slight improvement to consumer descriptions of DMTS.

Wordcloud of descriptors for geosmin

Wordcloud of descriptors for 2-MIB

Conclusions: Majority of subjects stated that the Drinking Water T&O Wheel would be helpful for describing one of the eight general categories of the odourants, and they believed that having a copy of the T&O Wheel present will improve their ability in identifying odours. With a few improvements to the T&O Wheel, that includes additional descriptors from the Odour Atlas, the T&O can serve as a valuable tool for consumers to use in describing nuisances in their drinking water. This study demonstrated that if proactive activities are introduced, like providing the T&O Wheel or training consumers with a lexicon of common descriptors for odours in drinking water, then consumers can provide more accurate and less variable descriptors for T&O problems in their drinking water.

References:

APHA (American Public Health Association), AWWA (American Water Works Association), and WEF (Water Environment Federation). 2012. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, 22nd ed. (Rice, E. W., Baird, R. B., Eaton, A. D., Clesceri, L. S. eds.) Washington DC.

Burlingame, G. A. & Mackey, E. D. 2007 Philadelphia obtains useful information from its customers about taste-and-odour quality. Water Science & Technology 55 (5), 257-263.

Burlingame, G. A. 2015 Earthy, with a Hint of Cucumber. An Environmental Scientist’s Journey into the Sensory World of Water. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. 130p.

Dietrich, A.M., Phetxumphou, K. & Gallagher, D.L. 2014 Systematic tracking, visualizing, and interpreting of consumer feedback for drinking water quality. Water Research 66, 63-72. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2014.08.007.law

Dietrich A.M. & Burlingame, G.A. 2015 Critical review and rethinking of USEPA secondary standards for maintaining consumer acceptability of organoleptic quality of drinking water. Environmental Sciences & Technology. DOI: 10.1021/es504403t, 49 (2), 708–720.

Drake, M. A. & Civille, G. V. 2003 Flavor Lexicons. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science & Food Safety 2 (1), 33–40. DOI: 10.1111/j.1541-4337.2003.tb00013.

Dravnieks, A. 1992 Atlas of Odours Character Profiles: ASTM DS61. American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM). Philadelphia, PA. USA. 352 p.

Gallagher, D.L. & Dietrich, A.M. 2014 Statistical approaches for analyzing customer complaint data to assess aesthetic episodes in drinking water. J. Water Supply: Research and Technology-AQUA. 63(5), 358-367.

Khiari, D., Barrett, S., Chinn, R., Bruchet, A., Piriou, P., Matia, L., Ventura, F., Suffet, I. H., Gittelman, T. & Leutweiler, P. 2002 Distribution Generated Taste-and-Odour Phenomena. Denver, CO: AwwaRF, 340 p.

Köster, E.P., Degal, J. & Piper, D. 2002 Proactive and retroactive interference in implicit odour memory. Chemical Senses 27(3), 91-206.

Köster, E.P. 2005 Does olfactory memory depend on remembering the odours? Chemical Senses 30 (suppl 1): 1236-1237.

Lawless, L. J. R. & Civille, G. V. 2013 Developing Lexicons: A Review. Journal of Sensory Studies DOI: 10.1111/joss.12050 28 (4), 270-281.

Mallevialle, J. & Suffet, I. H. 1987 Identification and Treatment of Tastes and Odours in Drinking Water, ISBN #0-89867-392-5. AWWA Research Foundation and Lyonnaise Des Eaux Cooperative Research Report, American Water Works Assoc., Denver, Colo., USA.

Meilgaard, M. C., Dalgliesh, C. E. & Clapperton, J. F. 1979 Progress towards an international system of Beer Flavour Terminology. American Society Brewing Chemistry 37, 42-52.

Piriou, P., Devesa, R., Puget, S., Thomas-Danguin, T. & Zraick, F. 2015 Evidences of regional differences in chlorine perception by consumers: Sensitivity differences or habituation? Journal of Water Supply: Research & Technology-AQUA 64 (7), 783-792.

Watson, S.B. & Jüttner, F. 2016 Malodourous volatile organic sulfur compounds: sources, sinks and significance in inland waters. Critical Reviews in Microbiology, in press.

Webber, M. A., Atherton, P. & Newcombe, G. 2015 Taste and odour and public perceptions: what do our customers really think about their drinking water? Journal of Water Supply: Research & Technology-AQUA, 64 (7), 802-811.

Yu, Y., An, W., Yang, M., Gu, J., Cao, N. & Chen, Y. 2014 Quick response to 2-MIB episodes based on native population odour sensitivity evaluation. Clean–Soil, Air, Water 42 (9), 1179-1184.