What’s in YOUR Water?

By Bastiana Rodebaugh – MPH Student

Bastiana Rodebaugh is a Master of Public Health student in the Population Health Sciences department, working with Dr. Pierson. Her concentration is in Infectious Disease, and areas of interest include biosecurity and food safety.

Where does your water come from?

Who manages your water supply?

Do you regularly test your water supply?

Is there a protection plan in place?

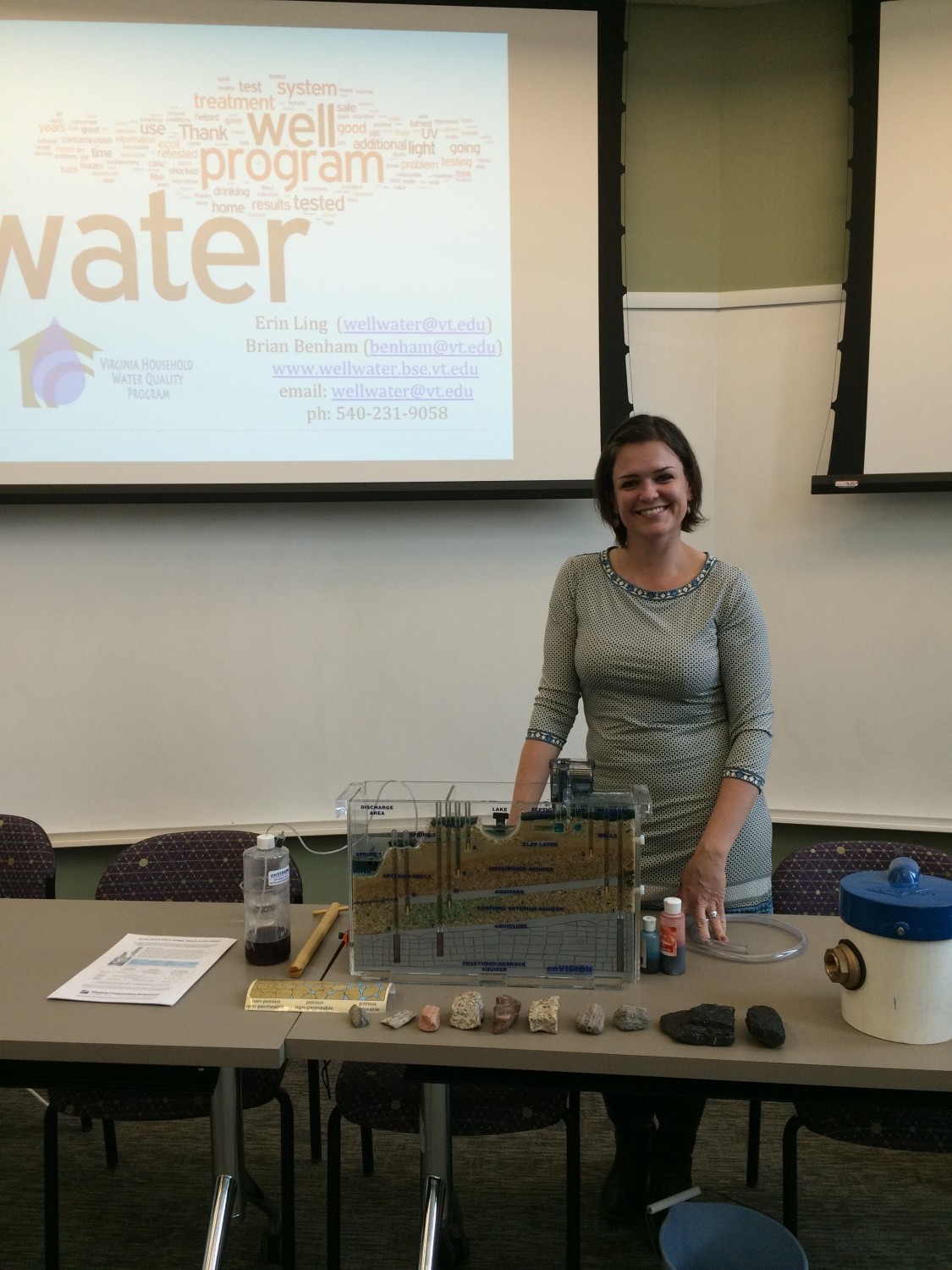

These are just a few of the questions that Erin Ling, Senior Extension Associate of the Virginia Tech Biological Systems Engineering, Virginia Cooperative Extension likes to ask her audience. Recently she asked graduate students in the Virginia Tech Water INTERface Water for Health Seminar Class those questions. For a surprising number of people, the answer is simply “I don’t know”.

Approximately 20% of Virginians rely on wells, springs and cisterns for their water supply. Springs and cisterns utilize surface water, while wells rely on ground water. Although most of us are aware of and understand the basic water cycle, ground water tends to be a mystery for many. We are able to access groundwater resources through wells by drilling (usually between 20 and 1,000 feet below the surface), and then pumping water to the surface for easy access. From the bottom of the well, water is taken in through an open borehole or a screen. While many contaminants are removed naturally through the “recharging” process, in which rain water and surface water percolate through soil, are purified, and replenish groundwater, there is still potential of microbial and chemical contamination.

In fact, 73% of personal water supply systems exceed EPA public health or nuisance standards, but many homeowners are not aware of this, and simply assume their water is clean. Although a water sample is required for testing when a well is initially drilled, many aspects of water quality can change due to alterations in the surrounding environment. For example, a neighbor’s use of chemicals, such as fertilizer or pesticide, may impact not only their groundwater but also the water supplies of those around them. In addition, construction of new developments and paved roads increase runoff and impact the amount of water that can be reabsorbed into the ground. In some cases, this may lead to insufficiently recharged groundwater sources and the need for new wells to be drilled (Ling, 2015).

Ling demonstrates these concepts using a small-scale model, which includes wells, lakes, and grass lawns, as well as changing topography. The miniature “wells” are tapped into replica ground water sources, through different layers of rock and sand. Using colored dyes, sources of “contamination” can be followed from one well to another, or from the surface to multiple ground and surface water sources. This represents real world scenarios, such as the use of fertilizers on a lawn. These chemicals not only affect the quality of ground water immediately below, but can also infiltrate nearby streams and lakes.

Watching this demonstration helps to drive home the point that we really do not know what is in our water unless we test it, and that the need for further treatment of home water resources may be necessary. But how do we determine if our water needs to be filtered, disinfected, or softened? Fortunately, the Virginia Household Water Quality Program has a way for us to assess this without breaking the bank! VAHWQP partners with Virginia Tech to provide testing of “house water” samples. Homeowners are able to bring in samples of their tap water and receive a full analysis and explanation for a very inexpensive $49.

Programs such as this are helping to promote awareness of where we get our water, what we may need to address within our local water supplies, and how our health can be affected by our water sources.

Citations

Ling, E. (Director) (2015, March 24). Household Water Quality. Lecture conducted for Water INTERface at Virginia Tech, Blacksburg VA.

For more about testing well water, go to http://www.wellwater.bse.vt.edu/events.php